Sometimes opera directors come up with a twist to a plot hat is illuminating without requiring pretzel logic to actually align it with the libretto. I think Jossi Wieler and Sergio Morabit’s production of Wagner’s Lohengrin for the Wiener Staatsoper in 2024 manages that pretty well.

Tag Archives: zeppenfeld

A Fidelio in two halves

I have long been of the opinion that Beethoven’s Fidelio is structurally flawed. The first and second acts are so different intone and dramatic intensity that it never seems quite to hang together. Tobias Kratzer obviously shares this view but being smarter than me finds a way to leverage it. For his production at the Royal Opera House in 2020 he takes the two acts and effectively makes the second a commentary on the first. It’s worth quoting his own words:

Like no other opera, Beethoven’s Fidelio falls into two unequal halves. Act I is a historical melodrama on freedom and love in the post-Revolutionary era. Act II is a political essay on the responsibility of the individual in the face of the silent majority, a musical plea for active empathy.

Tcherniakov’s Holländer

Dmitri Tcherniakov directed Der fliegende Holländer in Bayreuth in 2021 where it was recorded. It’s no surprise given (a)Tcherniakov and (b)Bayreuth that it’s not a straightforward production. I’m not sure I have fully unpacked it and there isn’t anything in the disk package to help (just the usual essay telling the reader what he/she/they already know/s).

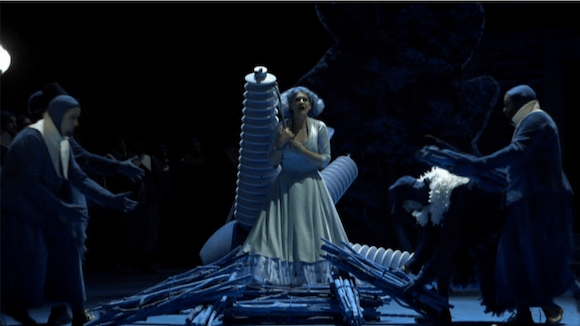

Make Brabant Great Again

Yuval Sharon’s Lohengrin in 2018 at the Bayreuth Festival was the first production there by an American director and, perhaps unsurprisingly, there are echoes of contemporary events in the US in the show. Specifically Sharon’s Brabant is a conformist theocracy in which society has regressed technologically. Some of the action takes place in and around a prominently placed disused electrical installation of some kind. The Brabanters are cowardly and subservient, initially to Telramund and then, equally, to Lohengrin. The advent of a charismatic leader. does not necessarily equate to liberation or full citizenship. Sharon also claims in his director’s notes that the real dissenter is Ortrud and that it is her actions that liberate Elsa and Gottfried. Whether the staging supports this is, I think, questionable.

Karajan’s Walküre – 50 years on

To quote a quite different opera, “it is a curious story”. In 1967 a production of Wagner’s Die Walküre, heavily influenced by Herbert von Karajan [1] who conducted the Berlin Philharmonic for the performances, opened the very first Osterfestspiele Salzburg. 50 years later it was “remounted” with Vera and Sonja Nemirova directing. I use inverted commas because it’s actually not entirely clear how much was old and how much new. It might be more accurate to describe it as a homage to the earlier version. In any event, it was recorded, in 4K Ultra HD, no less and released as one of the very first opera discs in that format.

Cogent Parsifal

Wagner’s Parsifal has been served rather well on Blu-ray and DVD in the last few years. The 2016 Bayreuth recording is another interesting addition to the list. Uwe Eric Laufenberg’s production is not exactly traditional but it’s not “in your face” conceptual either. The setting is contemporary and various visual clues locate it where Europe meets Asia; perhaps the Southern Caucasus. The grail temple is run down. There are soldiers and refugees and tourists, as well as the Grail knights. There’s plenty of Christian symbolism around. The “swan scene” is played straight. The “communion scene” uses Amfortas as the source of the communion blood; an idea which seems common enough. Here he’s wearing a crown of thorns (and not much else) and there’s lots of blood.

Elegant and subtle Otello

Vincent Brossard’s production of Verdi’s Otello for the 2016 Salzburg Easter Festival is both elegant and subtle; the latter quality being backed up by superb singing and acting from the principals. In many ways the production is clean and straightforward with a focus on character development but it also makes use of elegant lines and sharply contrasting darks and lights in creating the stage picture. There’s also a really cool use of mirrors during Già nella notte densa that I can’t quite figure out.

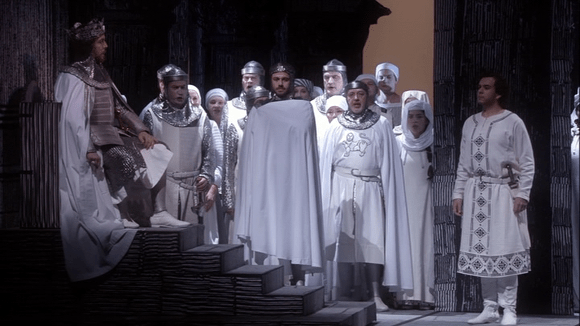

Moors and Christians

Schubert could write great melodies and he had a real affinity for the voice so one might expect him to have been successful when he turned his hand to opera. He wasn’t with Fierrabras which wasn’t performed until decades after his death and has been revived seldom since, most recently at Salzburg in 2014 where it was recorded. It’s easy to see why. The libretto is awful and even if the music were really amazing, which it isn’t but more of that later, I doubt it would have made much impact.

Der Freischütz in Dresden

At first blush Axel Köhler’s 2015 production of Weber’s Der Freischütz for Dresden’s Semperoper seems entirely traditional but as it unfolds it reveals some real depth that pretty much restores the sense of horror that the original audience felt. It’s set in an indeterminate time period in the aftermath of war. The first act looks quite conventional but there’s a very tense air to it with both sexuality and violence just below, and occasionally above, the surface. The atmosphere is greatly enhanced by our first look at Georg Zeppenfeld who is a very fine and rather plastic Kaspar. There are echoes here of his König Heinrich in Bayreuth.

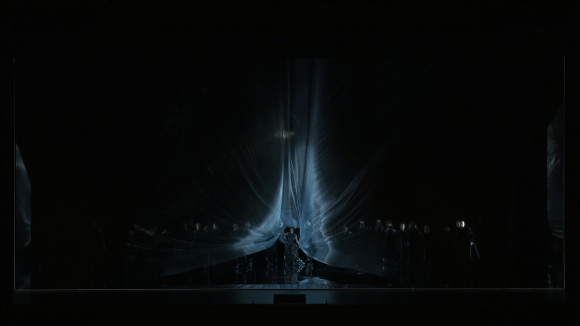

Rationing the rapture

Katharina Wagner’s take on Tristan und Isolde recorded at Bayreuth in 2015 is hard to unpack. There are some hints in a short essay in the booklet accompanying the disk and a few more in the interview with conductor Christian Thielemann included as an extra but it still leaves the viewer with a lot to do. It’s essentially unromantic and quite abstract. A lot of stuff that happens in a traditional interpretation just doesn’t happen but there’s not really anything much to replace it. What’s left is the story of two people who fall in love in a situation where that is bound to end badly and where, despite the best efforts of pretty much everyone else, it does. It’s actually quite nihilistic. Tristan, and maybe Isolde, seek a kind of transcendence in love/death but there is none. At the end Isolde doesn’t die but something in her does. It had me thinking of Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (but then so much in life does).