Katherina Thoma not unreasonably chooses to set her 2013 Glyndebourne production of Ariadne auf Naxos in a country house in the south of England (though I suppose equating the Christies with a rather boorish Viennese bourgeois might be thought a touch unkind). She also chooses to set it in 1940 which sets us up for an almost Marxian dialectic not just between high art and low art but between art and life; especially where life and death are concerned.

Tag Archives: roussillon

Ravel double bill

In 2012 Glyndebourne staged an interesting and contrasting double bill of Ravel one-acters in productions by Laurent Pelly. The first was L’heure espagnole. It’s a sort of Feydeau farce set to music. The plot is classic bedroom farce with the twist that most of the doors the lovers come in or out of belong to clocks. Concepción is the bored wife of a nerdy clockmaker. She’s not overly impressed by her two lovers; a prolix poet and a smug banker, who show up while hubby is out doing the municipal clocks. She’s much more taken by the slightly simple but very muscular muleteer who spends most of his time lugging lover infested clocks up and down stairs for her. Pelly wisely takes the piece at face value and brings off a mad cap forty five minutes timed to the split second.

Seamen from a distant Eastern shore

Berlioz’ Les Troyens is one of those pieces that really deserves the descriptor “sprawling epic” and, if anyone can make an epic sprawl it’s David McVicar. This production, recorded at the Royal Opera House in 2012, is typical of McVicar’s more recent work. It’s visually rather splendid and the action is well orchestrated but it’s short on ideas and long on McVicar visual cliches; acrobats, gore and urchins (but mercifully no animals). I don’t want to be too hard on McVicar. This piece is based on the sort of “Ancient History” one used to learn at prep school (British usage) and McVicar pretty much runs with that making no attempt to find deeper meaning, despite superficially translating at least the first two acts to the time of first performance; the era of European colonialism.

The ceremony of Innocence is drowned

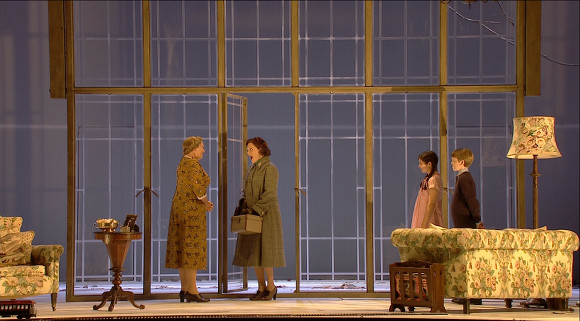

Jonathan Kent sets his 2011 Glyndebourne production of The Turn of the Screw in the 1950s. It’s effective enough especially when combined with Paul Brown’s beautiful and ingenious set and Mark Henderson’s evocative lighting. The set centres on a glass panel which appears in different places and different angles but always suggesting a semi-permeable membrane. Between reality and imagination? Knowledge and innocence? Good and evil? All are hinted at. A rotating platform allows other set elements to be rapidly and effectively deployed. There’s also a very clever treatment of the prologue involving 8mm home video.

Intense Dido and Aeneas

Deborah Warner’s entry point to Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas is the, almost certainly apocryphal, story about it premiering in a girls’ boarding school. At various points in the action we get a chorus of schoolgirls in modernish uniforms commenting silently on the action. They are on stage during the overture, are seen in dance class during some of the dance music and queue up for the Sailor’s autograph. It’s quite touching and adds to the pathos of the basic, simple, tragic story. Warner also adds a prologue (the original is lost). In Warner’s version Fiona Shaw declaims, and acts out, poems by Ovid/Ted Hughes, TS Eliot and WB Yeats. These additions aside the piece is presented fairly straightforwardly in a sort of “stage 18th century” aesthetic. The witch scenes are quite well handled with Hilary Summers as a quite statuesque sorceress backed up by fairly diminutive (and, for witches, quite cute) Céline Ricci and Ana Quintans. Their first appearance is quite restrained but they go to town quite effectively in their second appearance.

David McVicar’s Die Meistersinger

David McVicar chooses to set his production of Die Meistersinger, staged at Glyndebourne in 2011, in the 1820s or thereabouts. It’s an interesting choice as it puts German nationalism in a specifically cultural rather than political context and also rather clearly makes the point that “foreign rule” = “French rule”. That said, he really doesn’t develop any implications from that and what we get is a production typical of recent McVicar efforts. There’s spectacle aplenty and very good character development but he doesn’t seem to have any Big Ideas; for which, no doubt, many people will be grateful. The only place he seems to go a bit overboard is in laying on some fairly heavy German style humour. People who think that slapping waitresses on the bottom is the height of comedic sophistication will probably appreciate it.

Sex and violets

Cilea’s Adriana Lecouvreur isn’t performed very often and, when it is, it’s usually because some great diva of the day wants to do it. That’s the case with the 2010 Covent Garden production which was created by David McVicar for Angela Gheorghiu. Actually I am a bit surprised it’s not done more often. It’s not a great masterpiece but it’s no worse than a great many commonly done pieces and, if the plot is a bit implausible, it’s not as offensive as half of Puccini’s output. I would have thought it would have great appeal to that opera middle ground to which I don’t belong.

Adventure story

Robert Carsen doesn’t seem disposed to treat Handel too reverentially. Although there is some of the trademark Carsen cool minimalism in his 2011 Glyndebourne production of Rinaldo (not to mention symmetrically arranged furniture) there’s also a degree of humour, as there is in his Zürich Semele. I find it very effective and, judging by the audience reaction, so did the people who saw it at Glyndebourne.

Watery Kat’a Kabanová

Robert Carsen’s producton of Janáček’s Kat’a Kabanová is typically simple and elegant. Recorded at the teatro Real in Madrid it features a flooded stage with a large number of wooden pieces, like palettes, that are rearranged to form the set. At the beginning of Act 1 the pieces form a pathway through the water simulating the banks of the Volga. Later they are rearranged int a square at centre stage to represent the claustrophobic Kabanov house. All this rearrangement is done by the ladies of the chorus who roll around in the water in white shifts. No breaks are needed between scenes, just the intermezzi the composer provided for the purpose. A mirror at the back of the stage reflecting the water and an elegant and effective lighting plot complete the staging.

What’s green and blue and Carsen all over?

Robert Carsen’s production of Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream is as visually striking as any of his productions. It’s also one that’s done the rounds, playing in Aix and Lyon before being recorded by a strong cast at the Liceu in Barcelona in 2005. The challenge with Dream is to create visual worlds for the Fairies and the Mortals that are different but work together. Carsen and his usual design team do this very well in this case. The Fairies are given striking green and blue costumes with red gloves. The mortals mostly run to white and cream and gold and they seem to spend a lot of time in their underwear. The lighting, as always with Carsen, forms an important part of the overall design. Carsen completists will also notice certain other characteristic touches like starkly arranged furniture.