So it was back to the Bluma Appel on Thursday evening to see part 2 of Matthew López’ The Inheritance. Part 1 had certainly left plenty of active plot lines to be resolved (or not) so it looked like being an interesting ride.

So it was back to the Bluma Appel on Thursday evening to see part 2 of Matthew López’ The Inheritance. Part 1 had certainly left plenty of active plot lines to be resolved (or not) so it looked like being an interesting ride.

Tuesday’s lunchtime performance in the RBA was a preview of the upcoming Opera Atelier show All is Love which is essentially a remount of the February 2022 show that nobody much saw because it happened during a blizzard with most of downtown closed due to “trucker” activity.

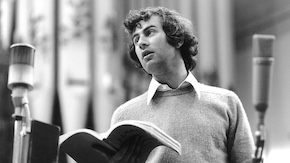

Iconic British countertenor James Bowman passed away last March. On Sunday night at Trinity-St. Pauls the Early Music folks at UoT presented a tribute to the man and his career. It was very well done. Music associated with Bowman; mostly Purcell and Britten, was interspersed with video and personal recollections/testimonials that fully reflected the considerable influence Bowman had on the English music scene and on the more widespread acceptance of the countertenor voice in the classical music world generally. Continue reading

Iconic British countertenor James Bowman passed away last March. On Sunday night at Trinity-St. Pauls the Early Music folks at UoT presented a tribute to the man and his career. It was very well done. Music associated with Bowman; mostly Purcell and Britten, was interspersed with video and personal recollections/testimonials that fully reflected the considerable influence Bowman had on the English music scene and on the more widespread acceptance of the countertenor voice in the classical music world generally. Continue reading

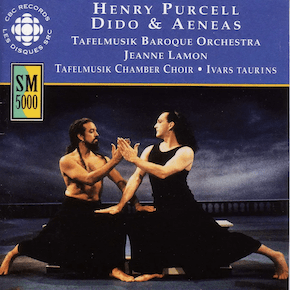

To round out this mini survey of the early discography of Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas I’m going to fast forward a bit to the 1995 recording by Tafelmusik. The most striking thing about this version is the very small instrumental ensemble; two violins, viola, violincello and harpsichord led by Jeanne Lamon. One quickly gets the feel for how they are going to perform with a very fast and rhythmically sprung overture.

To round out this mini survey of the early discography of Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas I’m going to fast forward a bit to the 1995 recording by Tafelmusik. The most striking thing about this version is the very small instrumental ensemble; two violins, viola, violincello and harpsichord led by Jeanne Lamon. One quickly gets the feel for how they are going to perform with a very fast and rhythmically sprung overture.

It’s perhaps a surprise then that Dido is sung by a very dark mezzo with some vibrato; Jennifer Lane. who also doubles up as the Sorceress. It does make for a very marked contrast with Ann Monyious’ quite bright Belinda. It also sounds like the full Tafelmusik Choir is used which is a much bigger group than Parrott uses. It’s also interesting to hear a young Russell Braun as a very characterful Aeneas.

And so we come to the third in our historical sequence of recordings of Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas. We are talking about Andrew Parrott’s recording with the Taverner Players and Choir recorded at Rosslyn Hill Chapel in 1981. It’s a record that I bought when it first came out and has been a point of reference for me ever since.

And so we come to the third in our historical sequence of recordings of Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas. We are talking about Andrew Parrott’s recording with the Taverner Players and Choir recorded at Rosslyn Hill Chapel in 1981. It’s a record that I bought when it first came out and has been a point of reference for me ever since.

It’s a consciously academic affair in some ways. It was produced in conjunction with an Open University course ; “Seventeenth Century England: A Changing Culture”. It’s also musicologically rooted in scholarship. The album booklet even lists the provenance of the instruments used; mostly modern copies of 17th century models and we are told that the work is performed at pitch A=403. The band and chorus are realistically sized; six violins, two violas, bass violin with bass viol, archlute and harpsichord continuo. A guitar is used in some of the dance numbers. The chorus is six sopranos; some of whom do double duty as witches, the Sailor and the Spirit, four tenors and two basses.

So, to continue our look at the recording history of Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas we turn to the 1961 Decca recording with Janet Baker in the title role. This has won so many awards and featured on so many “best of” lists that it might reasonably be considered to serve as some sort of “gold standard”. It’s certainly very good but I’m more interested in looking at what it says about the evolution of performance practice of Dido and Aeneas than in adding to the praise for Dame Janet’s performance.

So, to continue our look at the recording history of Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas we turn to the 1961 Decca recording with Janet Baker in the title role. This has won so many awards and featured on so many “best of” lists that it might reasonably be considered to serve as some sort of “gold standard”. It’s certainly very good but I’m more interested in looking at what it says about the evolution of performance practice of Dido and Aeneas than in adding to the praise for Dame Janet’s performance.

Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas has a long and dense history in the recording studio. The first recording dates back to 1935 and the vast stream of recordings since serve as a kind of barometer of the changes in style in performing 17th century music. I haven’t listened to every recording but I can look at four key moments in the discography and compare them. I’ve also listened or watched a fair number of fairly recent productions. The video review page has six entries for this work; all 1995 or later. There are also five reviews of live productions and reviews of several related shows. But for the purposes of this mini-project I’m going to look at four recordings that take us from the early 1950s to the mid 1990s. The four recordings are:

Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas has a long and dense history in the recording studio. The first recording dates back to 1935 and the vast stream of recordings since serve as a kind of barometer of the changes in style in performing 17th century music. I haven’t listened to every recording but I can look at four key moments in the discography and compare them. I’ve also listened or watched a fair number of fairly recent productions. The video review page has six entries for this work; all 1995 or later. There are also five reviews of live productions and reviews of several related shows. But for the purposes of this mini-project I’m going to look at four recordings that take us from the early 1950s to the mid 1990s. The four recordings are:

This post will deal with the first with subsequent posts on the others. Continue reading

Last night saw the first of two performances of Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas at Trinity-St. Paul’s. It was a collaboration between the UoT Schola Cantorum and the Theatre of Early Music though where one starts and the other ends I’m none too sure! Before the Purcell we got a fine performance of an early solo violin piece; Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber’s Passacaglia in G Minor played by Adrian Butterfield.

WILDWOMAN, by Kat Sadler (who also directed), is part of the {{her words}} festival at Soulpepper and I attended the first preview performance on Thursday night at the Young Centre. It’s not usual to review previews but I’m out of the country for most of the run proper so there it is. It’s an interesting piece. It weaves together two (more or less) real stories that are quite tenuously related into a single integrated narrative that explores humanity, power and the role of women in society.

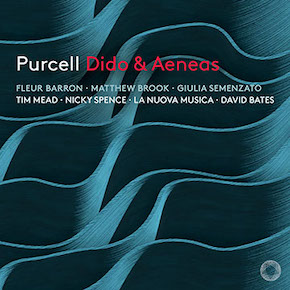

This new CD recording of Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas sets out to produce a version that might have been heard at court in the early 1680s. This is, of course, one of several theories about the work’s genesis and it’s the one I find most credible. Taking this as a starting point allows music director David Bates a framework in which to consider issues of style and casting.

This new CD recording of Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas sets out to produce a version that might have been heard at court in the early 1680s. This is, of course, one of several theories about the work’s genesis and it’s the one I find most credible. Taking this as a starting point allows music director David Bates a framework in which to consider issues of style and casting.

He posits significant French influence, which I would take as pretty much a given, but also some Italian flavour, which is a new idea to me and I think, too, that it’s clear that the Anglican choral tradition influences the choruses. So what does he do with these premises? First, and perhaps most importantly, he casts a rather dramatic mezzo, Fleur Barron, as Dido and encourages/allows her to present the role as if it were perhaps la grande tragédienne from one of Lully’s tragédies lyriques. Paired with the light, lyric soprano Giulia Semenzato as Belinda it produces an effect that strongly reminded me of Meghan Lindsay and Mireille Asselin in the recent Opera Atelier production though Semenzato ornaments more than most Belindas (and does it very well).