British soprano Mary Bevan and pianist Roger Vignoles gave a recital of French chansons in Walter Hall on Monday night. The concept was that the songs were paired; one being a setting of Baudelaire by a male composer and the other song by a female composer of the the same period. With two exceptions all the composers were French and with one exception from roughly the fin de siècle. So Duparc, Déodat de Séverac, Fauré Debussy and de Bréville were paired variously with the predictable; les sœurs Boulanger and Pauline Viardot, and less predictable; Mel Bonis, Marguerite Canal, Amy Beach (American) and Jeanne Landry (Canadian and much later).

Tag Archives: bevan

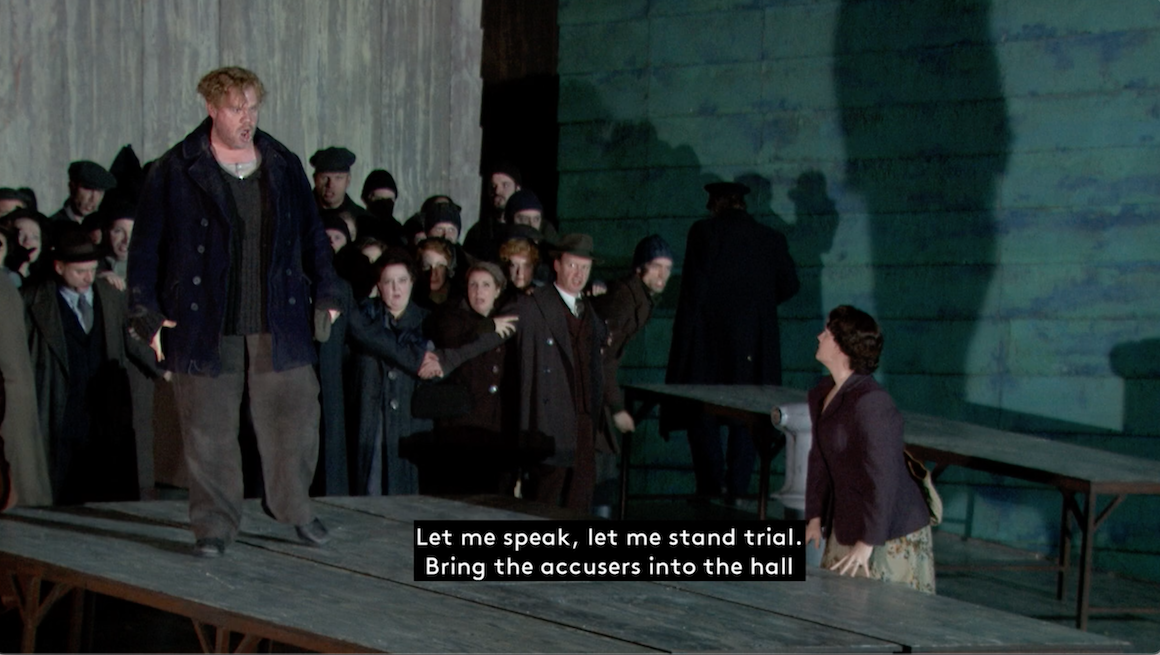

Skelton as Grimes

Continuing the theme of all Grimes, all the time… The only commercially available recording of Britten’s Peter Grimes with Stuart Skelton in the title role is a Chandos SACD recorded in Bergen in 2019 with Edward Gardner conducting and it’s really good. These two though had been captured on video in 2015 in a David Alden production at ENO. That had formed part of the ENO Live series of cinema transmissions but it was rebroadcast in August last year on Sky Arts in the UK. That version (at least my copy) is 720p video and AAC 2 channel 48kHz audio; so not quite Blu-ray standard but very tolerable.

Greene’s Jephtha

Fourteen years before Handel’s 1751 work Jephtha Maurice Greene produced a different English language oratorio on the same theme and with the same title. It’s now been recorded by the Early Opera Company.

Fourteen years before Handel’s 1751 work Jephtha Maurice Greene produced a different English language oratorio on the same theme and with the same title. It’s now been recorded by the Early Opera Company.

Thje story is taken from Judges and concerns the recall of Jephtha from exile to lead the Israelite army against an Ammonite invasion (the people from the East bank of the Jordan not the cephalopods). Jephtha promises Jehovah that if he is victorious he will sacrifice the first creature “of virgin blood” he meets (shades of Idomeneo) which, of course, turns out to be his daughter. There’s no divine intervention and no happy ending.

HIP à l’outrance

And so we come to the third in our historical sequence of recordings of Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas. We are talking about Andrew Parrott’s recording with the Taverner Players and Choir recorded at Rosslyn Hill Chapel in 1981. It’s a record that I bought when it first came out and has been a point of reference for me ever since.

And so we come to the third in our historical sequence of recordings of Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas. We are talking about Andrew Parrott’s recording with the Taverner Players and Choir recorded at Rosslyn Hill Chapel in 1981. It’s a record that I bought when it first came out and has been a point of reference for me ever since.

It’s a consciously academic affair in some ways. It was produced in conjunction with an Open University course ; “Seventeenth Century England: A Changing Culture”. It’s also musicologically rooted in scholarship. The album booklet even lists the provenance of the instruments used; mostly modern copies of 17th century models and we are told that the work is performed at pitch A=403. The band and chorus are realistically sized; six violins, two violas, bass violin with bass viol, archlute and harpsichord continuo. A guitar is used in some of the dance numbers. The chorus is six sopranos; some of whom do double duty as witches, the Sailor and the Spirit, four tenors and two basses.

Handel’s Serse from the English Concert

I don’t review a lot of full length audio only recordings of mainstream operas. Generally I think video makes more sense but sometimes something comes along that attracts my attention. The recent recording of Handel’s Serse by the English Concert with Harry Bicket was one such. This time it’s the cast that caught my attention. There’s Emily d’Angelo (are we allowed to call her “young” or “emerging” any more?) in the title role but also such fine Handel singers as Lucy Crowe as Romilda and Mary Bevan as Atalanta. As it turns out there’s not a weak link in the cast and while these three turn in fine performances so do Daniela Mack (Amastre), Paula Murrihy (Arsamene), Neal Davies (Ariodata) and William Dazeley (Elviro). Continue reading

I don’t review a lot of full length audio only recordings of mainstream operas. Generally I think video makes more sense but sometimes something comes along that attracts my attention. The recent recording of Handel’s Serse by the English Concert with Harry Bicket was one such. This time it’s the cast that caught my attention. There’s Emily d’Angelo (are we allowed to call her “young” or “emerging” any more?) in the title role but also such fine Handel singers as Lucy Crowe as Romilda and Mary Bevan as Atalanta. As it turns out there’s not a weak link in the cast and while these three turn in fine performances so do Daniela Mack (Amastre), Paula Murrihy (Arsamene), Neal Davies (Ariodata) and William Dazeley (Elviro). Continue reading

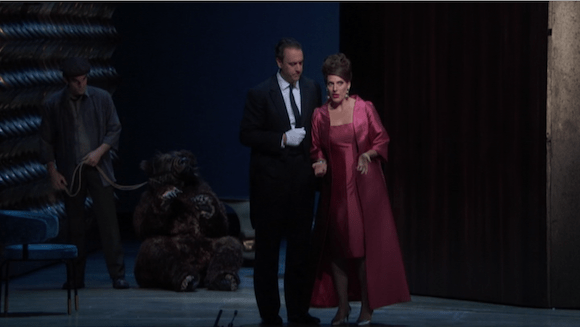

The end of all human dignity

Thomas Adès’ latest opera, The Exterminating Angel, is probably his most ambitious and best to date. It received its US premiere at the Met in 2017 and was broadcast as part of the Met in HD series, subsequently being released on DVD and Blu-ray. It’s based on the surrealist 1962 Buñuel film. It’s a very strange plot. A group of more or less upper class guests attend a dinner after an opera performance. All the servants except the butler have (inexplicably) left the house. The guests seem unable to leave the room they are in nor can anyone from outside enter it. This goes on for days(??) during which the guests accuse each other of various perversions including incest and paedophilia and turn violent while still expressing delicate aristocratic sensibilities like an inability to stir one’s coffee with a teaspoon. There’s a suicide pact, a bear and several sheep involved before the “spell” to escape the room is discovered. What happens afterwards is unclear. (The opera omits the closing scenes of the film). It’s very weird and quite unsettling; Huis Clos meets Lord of the Flies?

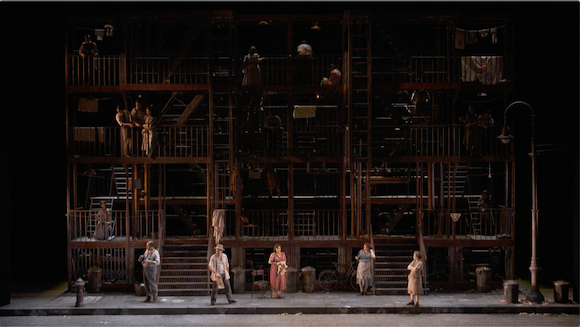

Street Scene in Madrid

It’s not easy to figure out how to stage Kurt Weill’s Street Scene. On the one hand it’s a gritty story of violence and poverty and hopelessness. On the other hand it’s got classic Broadway elements; romance, glitzy song and dance numbers etc. It’s also, cleverly and deliberately, musically all over the place with just about every popular American musical style of the period incorporated one way or another.

The clutter of bodies

The latest Handel oratorio to be given the operatic treatment by Glyndebourne is Saul, which played in 2015 in a production by Australian Barrie Kosky. It’s quite a remarkable work. The libretto, as so often the work of Charles Jennens, takes considerable liberties with the version in Samuel and incorporates obvious nods to both King Lear and Macbeth as well as more contemporary events. David’s Act 3 lament on the death of Saul, for instance, clearly invokes the execution of Charles I. What emerges is a very classic tragedy. Saul, the Lord’s anointed, is driven by jealousy and insecurity deeper and deeper into madness and degradation and, ultimately, death. This is the basic narrative arc of the piece.