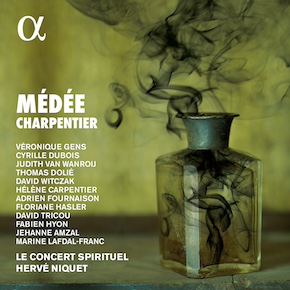

Cherubini’s Médée of 1797 is undergoing something of a revival at the moment albeit in an Italian version. But there’s an earlier and less known version of the same story with a libretto by (as opposed to based on) Corneille. It’s Charpentier’s Médée of 1693. It’s a tragédie lyrique with all the expected elements; an allegorical prologue in praise of Louis XIV, a classical subject, five acts, gods, spirits and demons and lots of spectacular theatrical effects. The Lully formula in fact. Continue reading

Cherubini’s Médée of 1797 is undergoing something of a revival at the moment albeit in an Italian version. But there’s an earlier and less known version of the same story with a libretto by (as opposed to based on) Corneille. It’s Charpentier’s Médée of 1693. It’s a tragédie lyrique with all the expected elements; an allegorical prologue in praise of Louis XIV, a classical subject, five acts, gods, spirits and demons and lots of spectacular theatrical effects. The Lully formula in fact. Continue reading

Tag Archives: van wanroij

Ariane

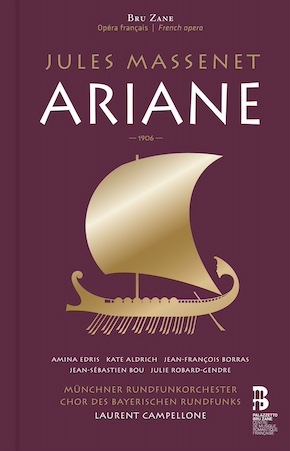

Ariane is a late opera (1906) by Jules Massenet. Now largely forgotten it has recently been recorded by the Palazzetto Bru Zane in their admirably produced series of French rarities. Unfortunately, unlike some of their other rediscoveries I wasn’t much taken with it.

Ariane is a late opera (1906) by Jules Massenet. Now largely forgotten it has recently been recorded by the Palazzetto Bru Zane in their admirably produced series of French rarities. Unfortunately, unlike some of their other rediscoveries I wasn’t much taken with it.

The plot is an odd take on the Theseus and Ariadne story. Ariadne helps Theseus defeat the Minotaur then sails away with him to Naxos taking her sister Phaedra with them. Phaedra and Theseus fall in love and Ariadne is devastated. When Phaedra learns what effect she has had she curses Aphrodite and attacks a statue of Adonis with a rock. Aphrodite causes the statue to fall on and kill her. This is rather more revenge than Ariadne wants so she goes down to the Underworld and trades a bunch of roses to Persephone for Phaedra. On returning to the light Phaedra vows to give up Theseus but it doesn’t stick and she and Theseus set off for Athens. Ariadne drowns herself. Continue reading

Intense Dido and Aeneas

Deborah Warner’s entry point to Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas is the, almost certainly apocryphal, story about it premiering in a girls’ boarding school. At various points in the action we get a chorus of schoolgirls in modernish uniforms commenting silently on the action. They are on stage during the overture, are seen in dance class during some of the dance music and queue up for the Sailor’s autograph. It’s quite touching and adds to the pathos of the basic, simple, tragic story. Warner also adds a prologue (the original is lost). In Warner’s version Fiona Shaw declaims, and acts out, poems by Ovid/Ted Hughes, TS Eliot and WB Yeats. These additions aside the piece is presented fairly straightforwardly in a sort of “stage 18th century” aesthetic. The witch scenes are quite well handled with Hilary Summers as a quite statuesque sorceress backed up by fairly diminutive (and, for witches, quite cute) Céline Ricci and Ana Quintans. Their first appearance is quite restrained but they go to town quite effectively in their second appearance.