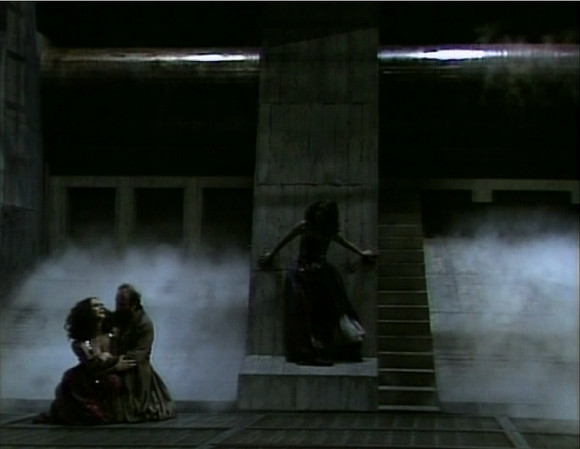

Chéreau’s Siegfried is even less obviously “industrial” than his Die Walküre. There’s a forge of course but there rather has to be. Other than that we get workshop, forest and lair pretty much as one might imagine until, of course, we end up back at the ruin where Brünnhilde waits. Brian Large injects lots of smoke at every opportunity.

Tag Archives: bayreuth

Chéreau Ring – Die Walküre

The second instalment of Patrice Chéreau’s 1980 Bayreuth Ring cycle is set, like Das Rheingold, in a sort of industrial bourgeois late 19th century. One would almost say steampunk if that were not an anachronism. Actually the “industrial” side is much less evident than in the earlier work. There’s a sort of astrolabe/pendulum thing in Valhalla but that’s about it. Setting aside, the story telling is very straightforward; so much so that it takes a real effort of the imagination to get into a mindset where this production could ever have been considered controversial. It’s quite literal; Brünnhilde has a helmet and breast and back plates (worn over a rather severe grey dress), Wotan has a spear, Siegmund has a sword. There’s not an assault rifle or light sabre to be seen. It is though dramatically effective.

Chéreau Ring – Das Rheingold

So much has been written about Patrice Chéreau’s centenary production of the Ring cycle at Bayreuth that I approached reviewing it with some trepidation. I have decided to write about it “as is”; i.e. to write about what I see on the DVD and leave the undoubted historical significance, perhaps even revolutionary impact of the production, to others. Also, it’s apparent that what’s on the DVD, filmed in an empty house as was contemporary Bayreuth practice, must differ from what was seen on the Green Hill in certain key ways. This is a review of what;s seen and heard on the DVD.

Curiously aloof Tristan

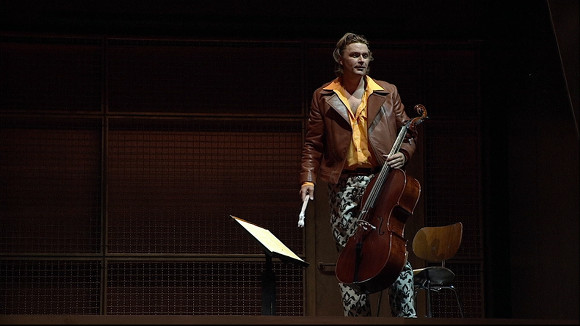

Christoph Marthaler’s 2009 Bayreuth production of Tristan und Isolde is set in a sort of Stalinist brutalist aesthetic populated with stock figures from the 1950s. Passion is at a minimum and the characters all seem to be trying as hard as possible to be conventional representatives of their roles. The only one who shows any real human engagement is Kurwenal who comes across almost as a commentator on the action, or even a director. There’s also some fairly stylized gesturing in a sort of pseudo-Sellars manner. It’s epitomised by the costumes in Act 2 where Isolde and Brangäne look like dolls dressed as Hausfraus and Tristan wears a hideous blue blazer. This is all rather reinforced by Michael Beyer’s video direction which uses a lot of close ups but also has a curious stillness about it that seems to amplify the emotional void; if indeed one can amplify a void. Oddly though, in places this approach really works in that the distance, coupled with very precise blocking, gives space for the music’s essential intensity to come through. Act 2 Scene 2, perhaps the emotional crux of the piece, is very moving and the So stürben wir, um ungetrennt is quite impressive.

Kupfer/Barenboim Ring – 4. Götterdämmerung

I think it’s only with the final instalment of the Kupfer/Barenboim Ring that its true power is apparent. The first three instalments are very fine but Götterdämmerung is devastating. All the elements that have been progressively introduced are seamlessly combined. Add to that extraordinarily intense performances from Siegfried Jerusalem (Siegfried), Philip Kang (Hagen) and, above all, Anne Evans (Brünnhilde) and one has something very special indeed.

Kupfer/Barenboim Ring – 3. Siegfried

We seem to be in some kind of post apocalyptic wasteland. Mime’s hut looks like a re-purposed storage tank but the bear and the forest are more or less realistic. It’s all very dark and there’s quite a lot of use of pyrotechnics. This is also our first look at Siegfried Jerusalem’s Siegfried and he is very good indeed. He captures the hero’s youthful vigour and arrogance extremely well. There is a strong performance too from a rather manic Graham Clark as Mime and John Tomlinson continues as a reckless and wild Wanderer.

Kupfer/Barenboim Ring – 2. Die Walküre

The Kupfer/Barenboim Ring continues very strongly with the second instalment, Die Walküre. It opens in quite a straightforward, more or less realistic way. Hunding’s hall is slightly abstracted with a recognizable tree. It’s quite spare though which creates space for the strong interpersonal dynamics between Siegmund and Sieglinde. Poul Elming is a very physical, almost manic Siegmund and Nadine Secunde’s Sieglinde is almost as physical. It’s all very intense and beautifully sung. Matthias Hölle as Hunding is no slouch either.

Kupfer/Barenboim Ring – 1. Das Rheingold

The 1991 Bayreuth Ring cycle is one of those productions that has become a historical landmark, as much as Chereau and Boulez’ 1976 effort, or maybe even more so. For many people it is the Ring. So what is it like? The staging is very bare and much reliance is placed on effects like lasers and smoke. It also makes considerable acting and athletic demands on the singers. It is, in many ways, a very modern production for 1991.

Can Bayreuth really tackle Meistersinger?

Die Meistersinger is a problematic opera, particularly for Bayreuth. It has rather disturbing elements of German nationalism and a performance tradition at the festival of those being used for ends that most people would rather be able to forget. No surprise then that Katharina Wagner’s production, recorded in 2008, tries to deal with both. It’s a bold effort. Like Robert Carsen’s Tannhäuser it tries to use visual art as a metaphor for music and art in general.

There were rats

I guess Lohengrin is one of those operas that’s so loaded up with symbols it just begs directors to deconstruct it. Well that’s what Hans Neuenfels’ Bayreuth production, recorded in 2011, does and then some. There is so much going on in this production that I think it would take many viewings to really get inside it. The bit most critics have fastened on is the costuming of the chorus as rats or, on occasion, half rat, half human. It’s visually interesting and since there are also ‘handlers’ in Hazmat suits it’s clear that some sort of experiment is being alluded to. Add in bonus rat videos at key points and there’s a lot to think about. One thing this does do is solve the Teutonic war song problem. A chorus of rather timid looking rats singing with martial ardour is a good deal less Nurembergesque than a similar chorus in armour or military uniforms. Rats aside the story is really told in a quite straightforward and linear way while providing all sorts of moments that one might want to interrogate further,