Overall I rate this cycle very highly. Andreas Homoki’s production is unusual in that it’s really not conceptual and is often very literal. That’s rare in Wagner productions in major European houses. But it’s also not cluttered up with superfluous 19th century “stuff”. When a thing is essential, it’s there as described. If it’s not essential more often than not it’s omitted.

Tag Archives: vogt

Zürich Ring – Götterdämmerung

And so to the final instalment… We open with the Rock but now the background room; while still the same 18th/19th century mansion, looks a bit the worse for wear with peeling and cracked paint. The Norns, predictably, are all in white. It’s all pretty conventional but done well.

Zürich Ring – Siegfried

Siegfried has been described as the scherzo of the Ring cycle and Andreas Homoki seems to have at least partly run with that. There are quite a few places, including some less obvious ones, where he seems to be going for laughs. The obvious ones are obvious enough. You can’t really have a bear in the first scene without it being comic but there were also times when Wanderer was camping it up a bit. We’ll come back to that.

Pogner’s Conservatory

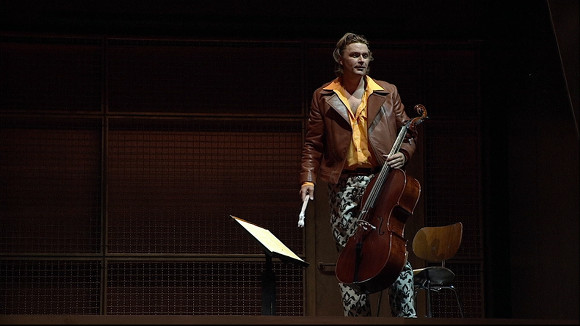

How to portray a group of people obsessed with music in a rather formalistic and rules driven way like the characters in Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg? The directorial team of Jossi Wieler, Sergio Morabits and Anna Viebrock, for their production at t6he Deutsche Oper Berlin in 2022, decided that the answer was to set it in a Conservatory.

Tcherniakov’s Khovanshchina

Mussorgsky’s Khovanshchina is a bit of a weird opera. It’s ostensibly based on a series of not entirely related events that unfolded during the succession crisis following the death of Tsar Fyodor III (which took about 12 years to play out) into a story that takes place in a day. It’s complicated by the fact that key players in the story; the Tsars Peter and Ivan and the Tsarevna Sofia don’t actually appear because the Russian censorship would not allow members of the dynasty to be portrayed on stage. Perhaps unsurprisingly Tcherniakov isn’t much interested in the details of the history and uses it to make some, not always entirely obvious, points about modernity vs tradition, personal power and the nature of religious cults.

Cogent Parsifal

Wagner’s Parsifal has been served rather well on Blu-ray and DVD in the last few years. The 2016 Bayreuth recording is another interesting addition to the list. Uwe Eric Laufenberg’s production is not exactly traditional but it’s not “in your face” conceptual either. The setting is contemporary and various visual clues locate it where Europe meets Asia; perhaps the Southern Caucasus. The grail temple is run down. There are soldiers and refugees and tourists, as well as the Grail knights. There’s plenty of Christian symbolism around. The “swan scene” is played straight. The “communion scene” uses Amfortas as the source of the communion blood; an idea which seems common enough. Here he’s wearing a crown of thorns (and not much else) and there’s lots of blood.

Vogt and Nylund bring dead city to life

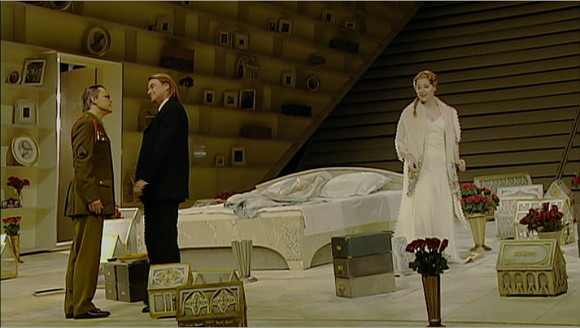

Kasper Holten shows his customary inventiveness in his production of Korngold’s Die Tote Stadt, recorded at Finnish National Opera in 2010. He places the whole opera inside Paul’s “Marie museum” with a chaotic, higgledy, piggledy model of the the city of Brugge as a back wall. He emphasises the dream elements of acts 2 and 3 through devices such as having the troupe of players and their boat emerge through Paul’s bed or assorted ecclesiastics popping up randomly in the “city model”. He also inserts a non-speaking Marie who is present throughout the piece, often to very interesting effect.

Can Bayreuth really tackle Meistersinger?

Die Meistersinger is a problematic opera, particularly for Bayreuth. It has rather disturbing elements of German nationalism and a performance tradition at the festival of those being used for ends that most people would rather be able to forget. No surprise then that Katharina Wagner’s production, recorded in 2008, tries to deal with both. It’s a bold effort. Like Robert Carsen’s Tannhäuser it tries to use visual art as a metaphor for music and art in general.

There were rats

I guess Lohengrin is one of those operas that’s so loaded up with symbols it just begs directors to deconstruct it. Well that’s what Hans Neuenfels’ Bayreuth production, recorded in 2011, does and then some. There is so much going on in this production that I think it would take many viewings to really get inside it. The bit most critics have fastened on is the costuming of the chorus as rats or, on occasion, half rat, half human. It’s visually interesting and since there are also ‘handlers’ in Hazmat suits it’s clear that some sort of experiment is being alluded to. Add in bonus rat videos at key points and there’s a lot to think about. One thing this does do is solve the Teutonic war song problem. A chorus of rather timid looking rats singing with martial ardour is a good deal less Nurembergesque than a similar chorus in armour or military uniforms. Rats aside the story is really told in a quite straightforward and linear way while providing all sorts of moments that one might want to interrogate further,

A grim and gritty Rusalka

Martin Kušej’s 2010 production of Dvořák’s Rusalka at the Bayerisches Staatsoper is exactly the sort of production traditionalists fume about over their port and cigars. It’s loosely based on the Fritzl and Kampusch imprisonment/child abuse cases. The Water Goblin, aided by his wife, Ježibaba, have their children; Rusalka and her sisters, imprisoned in a wet cellar under their house. The Water Gnome is clearly indulging in sexual abuse of the girls to the total indifference of his wife. Rusalka dreams of a life among humans and of love. She begs her mother to make her human/set her free. This happens and Rusalka, mute and tottering on red heels, is free to pursue her romance with the prince. Is this literal or all in Rusalka’s imagination? Does it matter? Continue reading